The practice of abstaining from meat in the Catholic faith has deep historical and spiritual roots. It is tied to the Church’s penitential traditions, which date back to the early Christians. Inspired by Jesus’ 40 days of fasting in the desert, early Christians adopted various forms of penance, including fasting and abstinence, as acts of devotion and repentance.

The Didache, also known as “The Teaching of the Twelve Apostles,” is one of the earliest Christian texts, dating back to the late 1st or early 2nd century. It is believed to be the training manual for the early priests compiled from the apostles. While it doesn’t explicitly mention abstinence from meat in the way later Church traditions do, it does emphasize fasting and moral discipline. For example, it instructs Christians to fast on Wednesdays and Fridays, distinguishing their practices from those of the “hypocrites,” likely referring to certain Jewish or pagan customs.

The text also encourages believers to abstain from “fleshly and bodily lusts,” which could be interpreted broadly to include acts of self-denial, such as fasting or abstaining from certain foods. This reflects the early Christian focus on spiritual growth through discipline and simplicity.

St. Basil of Caesarea (4th century) emphasized fasting and abstinence as spiritual disciplines, linking them to a broader call for moral and spiritual renewal. He described fasting as not merely abstaining from food but also from anger, desires, and falsehoods.

Abstinence from meat became particularly significant because meat was considered a luxury in ancient times. By forgoing it, Christians expressed sorrow for sin, practiced self-denial, and united themselves with Christ’s suffering on the cross. Fridays were chosen for this practice as a way to commemorate the day of Jesus’ crucifixion.

Over time, the Church formalized these practices. During the medieval period, abstinence from meat was observed more strictly, often extending to other animal products like eggs and dairy. The Council of Trent (1545–1563) emphasized abstinence as a universal penance, uniting Catholics worldwide.

In modern times, Pope Paul VI’s 1966 apostolic constitution “Paenitemini”, meaning to repent or do penance, allowed for adaptations to these practices. While abstinence from meat on Fridays remains a laudable tradition, Catholics can now substitute it with other acts of penance or charity, depending on local guidelines.

The distinction between meat and fish in Catholic dietary practices is rooted in historical, cultural, and theological factors. In the ancient Mediterranean world, where these practices developed, meat, particularly from land animals, was considered a luxury. It was associated with feasting, wealth, and celebration. Fish, on the other hand, was more commonly available, especially to communities near rivers or the sea, and was viewed as a simpler, humbler food.

Fish holds a special place in Christian symbolism. In the early Church, the fish became a symbol of Christ and faith. This association might have reinforced the inclusion of fish as an acceptable food during fasting and abstinence periods. Fish provides an accessible source of nutrition that could sustain people during fasts.

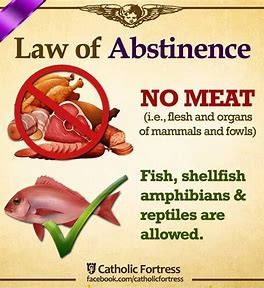

The Church doctrine historically defined “meat” as the flesh of warm-blooded animals. Fish and reptiles, like alligators and turtles, being cold-blooded, were categorized separately. This distinction became a guiding principle for fasting and abstinence rules.

Together, these factors shaped the tradition where fish was permitted while abstaining from meat.

If this is my last post, I want all to know there was only one purpose for all that I have written; to have made a positive difference in the lives of others. Anthony “Tony” Boquet, the author of “The Bloodline of Wisdom, The Awakening of a Modern Solutionary”